Rooted in sustainability: Agroforestry and sustainable agriculture in the UK

In the UK and worldwide, one of the most widely agreed and fundamental causes of habitat degradation and subsequent biodiversity loss is intensive farming, adversely affecting the ecosystems these practices inhabit. This frequently relies on the concentrated utilisation of land, water and agrochemicals, putting severe pressure on natural resources and reducing flora in agricultural systems where broad-spectrum herbicides are typically employed to control weeds and grasses that compete with crops.

The detrimental effects of intensive agriculture

The 19th and 20th centuries witnessed a significant transformation in agriculture due to the continued mechanisation and reduced processing costs; these advancements spurred the intensification of farming practices, with “yield per land” units radically increased through novel techniques, seed stocks and cultivars. Following WWII, agriculture burgeoned as an exceptionally profitable economic sector due to the emergence and rapid development of global food chains, increasing market competition, expanding industrial processes and intensive productivity. Subsequently, technological innovations emerged alongside the introduction of synthetic fertilisers enriched with key nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium aimed at maximising crop yields.

However, during this period concerns began to surface regarding the adverse consequences of intensive farming; issues including soil compaction, erosion and declining fertility became increasingly evident, in part attributed to the use of ammonium nitrate. These cumulative issues posed a threat to the sustainability of agriculture, developing the potential to detrimentally impact food supply chains, resulting in a substantial source of environmental and sustainability issues in Europe and worldwide. The cumulative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, current geopolitical shifts and various socio-economic patterns have foregrounded agriculture and food systems. In light of these challenges, reassessing and reorganising agriculture and food systems is critical to assure their resilience and sustainability.

Food insecurity in the UK

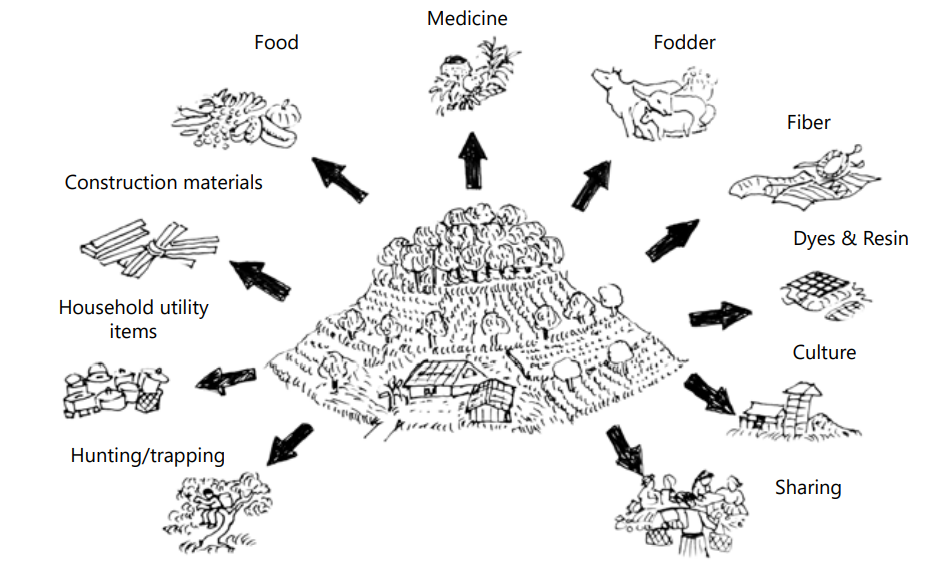

The food poverty rate of the UK is one of the most inflated in Europe; despite being the sixth wealthiest nation globally, a significant number of people are unable to obtain sufficient sustenance - according to recent governmental data, 4.2 million individuals (6%) were residing in a state of food poverty in the period between 2020-2021. Moreover, the “cost of living” crisis is significantly influencing the problem, with 9.3 million adults experiencing some form of food insecurity in January 2023, as reported by the Food Foundation (17.7% of all households). In an era of uncertain food security, it is perhaps unrealistic to expect intensive farming to be radically devolved. However, a creative “rethinking” of food systems with a strong emphasis on ecological quality is not unfeasible, with a focus on food security, sustainability and social benefits. In Europe, raw materials power economies, while in many developing countries they continue to serve as sustenance, providing the basis for many people’s livelihoods (See Figure 1 below). Therefore, we must find novel means of preserving the resources that underpin human development.

Figure 1: Potential forest products derived from agroforestry. Source: Xu et al, 2013.

Agroforestry: The benefits of trees on crops

A centuries-old means of production is being increasingly discussed as a potential solution that augments food production while enhancing ecological balance: agroforestry. Agroforestry has emerged as a viable solution that harmoniously incorporates trees into agricultural systems, fostering a mutually beneficial relationship between nature and cultivation. The practice is defined (by Hislop and Claridge) as a “collective name for land-use practices where trees are combined with crops and/or animals on the same unit of land (with) significant ecological or economic interactions between the tree and the agricultural components.”

As a fundamental introduction, 5 types of agroforestry as defined by Lancaster Farming include:

Alley cropping: The strategic planting of food crops in between rows of trees to generate income while the trees reach maturity - this particular system can yield a variety of products simultaneously, including fruits, vegetables, grains, flowers and bioenergy crops.

Silvopasture: The practice of grazing livestock under the shade of trees; this provides shelter for animals and generates revenue through the cultivation of crops or timber. Advocates of silvopasture hold a preference for integrating trees into pastures instead of allowing livestock to roam freely in woodlots, as the latter can potentially be detrimental to forest ecosystems.

Forest farming: The cultivation of high-value crops - particularly in a tropical forest context - such as ginseng, goldenseal, mushrooms and decorative ferns within a carefully managed tree canopy; these crops have become scarce in their natural habitats and are typically protected by laws prohibiting their wild harvesting.

Riparian buffers: The preservation of natural or planted strips of trees, shrubs, and other vegetation along rivers or streams - this conservation practice serves myriad purposes, including the prevention of erosion and nutrient runoff, the provision of wildlife habitats and the potential production of berries, nuts and decorative or bioenergy crops.

Windbreaks: The deliberate planting of trees or other plants to protect crops, animals, buildings and soil against the elements.

The classifications of different types of agroforestry are varied and complex; a full guide to agroforestry and its myriad practices adapted to a UK context can be found here. Agroforestry is an agroecological approach: agroecology promotes the conservation of soil and organic matter and other resources such as energy and water through systems that are productive but also resource-conserving.

The overarching benefits of agroforestry

Agroforestry is a practice rooted in the wisdom of indigenous communities and traditional farming and involves the intentional combination of trees, crops, and sometimes livestock on a singular piece of land. This integrated approach offers myriad benefits that range from ecological restoration to economic stability (particularly for rural communities). In the UK, where both agriculture and forestry have deep historical roots, the adoption of agroforestry is a natural progression that holds immense potential for:

1. Biodiversity enhancement.

Conventional monoculture agricultural practices frequently result in habitat destruction and a decline in biodiversity; conversely, agroforestry systems emulate natural ecosystems, providing diverse habitats for various species and limiting species extinction in both tropical and temperate climes. This promotes the conservation of native flora and fauna, contributing to the overall health of ecosystems.

The ecosystems provided by agroforestry support some species that control pests, thus assisting their predation and reducing the necessity for chemical pest control.

Trees within agroforestry systems provide food and shelter for pollinators including bees, butterflies and birds, boosting the pollination of crops and wild plants.

Agroforestry builds a healthy soil ecosystem that fosters microbial diversity - these organisms encourage nutrient cycling, decomposition and disease suppression, contributing to the wider health of ecosystems.

Agroforestry preserves genetic diversity by incorporating a mix of plant, tree, and crop species, assisting them to adapt to changing environments and resist diseases.

2. Soil biodiversity and rejuvenation.

Trees within agroforestry systems offer multiple advantages for improved soil health:

Improved soil quality. Tree roots assist in binding soil particles, reducing erosion and improving soil structure; fallen leaves and organic matter from trees create a natural mulch that enriches the soil, enhancing its fertility and water-holding capacity.

Reduced soil erosion and compaction. In agroforestry systems, trees and shrubs act as natural windbreaks and barriers that mitigate soil erosion driven by water runoff, with root systems binding soils, reducing compaction and improving soil structure.

Improved soil fertility. Agroforestry often includes nitrogen-fixing plants such as leguminous trees and cover crops which enrich soil, increasing fertility through the provision of essential nutrients.

Enhanced organic matter. Dead leaves, branches and other debris from trees contribute to increased organic matter content in soil; this improves soil structure, water retention and nutrient composition in which microorganisms flourish.

Biodiversity and pest management. Agroforestry promotes diversity in landscapes, creating the environmental conditions for beneficial birds and insects that control invasive pest populations, thus reducing the necessity for chemical interventions that detrimentally affect soil health.

Nutrient cycling. Trees and crops facilitate nutrient cycling by interacting with each other. The mycorrhizal network in woodland systems also shares nutrients and information so linking habitats is critical.

3. Climate resilience and carbon sequestration.

In light of the climate crisis, carbon sequestration has become a crucial endeavour to maintain the global temperature increase below 1.5°C versus higher levels.

Trees have an innate ability to capture carbon dioxide through the process of photosynthesis; agroforestry systems mitigate carbon whilst amplifying the sequestration potential of agricultural land, making it vital to combat climate change.

The unpredictable weather patterns associated with climate change pose a significant threat to agriculture. Agroforestry systems act as natural buffers, mitigating the impact of extreme weather events. Trees provide windbreaks that protect crops, reduce water runoff and regulate temperature, creating microclimates that are more stable and conducive to growth (see below).

There are substantial global opportunities offered by agroforestry on abandoned croplands to reduce net greenhouse gas emissions, detailed in a recent paper by Almaraz et al.

4. Increase in productivity.

Agroforestry offers the potential to boost agricultural output by adeptly incorporating trees, crops and diverse plant life in synchronicity. In addition, the overarching benefits can include:

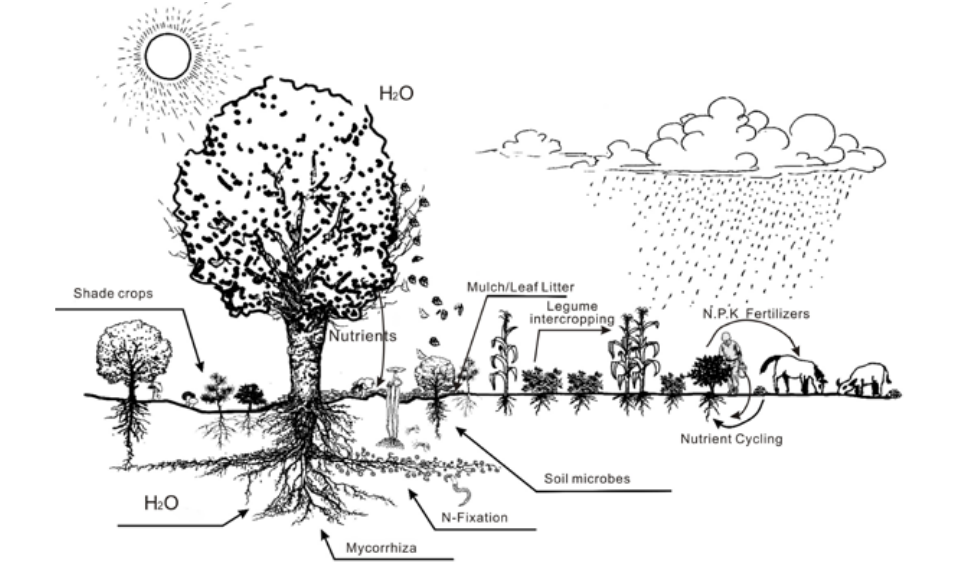

Enhanced nutrient cycling. Trees in agroforestry contribute organic matter that enriches the soil, boosts nutrient availability, promotes healthy plant growth and improves soil structure (see Figure 2 below); tree roots prevent soil erosion and compaction allowing plants to access nutrients and water supporting higher yields.

Diverse microclimates. Trees provide shading and windbreaks creating microclimates that protect crops from weather extremities. This enables crop cultivation and extends growing seasons.

Biological pest control. Agroforestry can control pest outbreaks thereby causing less damage to crops and contributing to higher yields. A rich variety of plants, insects, and predators plays a crucial role in maintaining a robust and balanced food chain; this stands in stark contrast to monoculture crops, where the prevalence of pests can lead to the necessity of ongoing technological and pest control interventions, incurring significant costs for farmers. These practices can result in substantial profits for large agricultural corporations while simultaneously contributing to the development of biological deserts; this issue is not limited to the United Kingdom - it affects regions worldwide.

Increased pollination. Trees and flowering plants attract pollinators thereby resulting in higher fruit and seed production, resulting in greater yields.

Shade-tolerant crops. Cultivating shade-tolerant crops enhances the efficiency of land utilisation while optimising productivity.

Figure 2: Nutrient cycles in typical agroforestry systems. Source: Xu et al, 2013.

5. Sustainable yield.

One of the most beneficial aspects of agroforestry is its capacity to generate multiple products from a singular piece of land; farmers can cultivate crops, harvest timber, and gather fruits or nuts from trees, diversifying income sources. This enhanced resilience reduces dependency on a single product and bolsters the economic stability of farming communities:

Provision of diverse products. Agroforestry systems yield a variety of products such as timber, fruits, nuts, medicinal plants and fodder. These products can be sold in various markets, adding to the income.

More stable food security. The world today is looking into investing in ancient systems of agroforestry to create sustainable solutions for the environment. This could provide better access to nutritional and food security and better livelihoods for millions of farmers.

Integration of livestock. Agroforestry incorporates forage crops and fodder trees providing supplement feed for livestock through which income can be generated.

6. Water management.

Trees perform an essential role in the regulation of water cycles; their roots help to prevent soil erosion, allowing for improved infiltration and reduction in the risk of flooding. Moreover, trees contribute to better water quality by filtering pollutants and contaminants from runoff.

7. Sociocultural benefits and community cohesion.

Agroforestry often necessitates collaboration among farmers, landowners and communities - shared knowledge, labour, and resources foster a sense of belonging and mutual support. This social aspect enhances rural livelihoods and promotes a sense of collective responsibility for the land.

Further reading - Agroforestry project - 9Trees CIC

The UK’s historic legacy of agroforestry practices

Agroforestry has been practised globally for thousands of years, with the management of trees, food crops, and domestic animals on a specific area of land widespread. Nonetheless, the exploration of agroforestry from a scientific perspective remains relatively recent; the concept of ‘agroforestry’ and its term was introduced in 1977 to characterise the amalgamation of trees and agricultural practices. In a historical context, extensive regions in central Europe were once rich with fruit and nut silvoarable systems until the past century, with evidence of agroforestry practices and variants existing in southern Italy, north-east France, the Netherlands, northern Spain, eastern Germany, Greece and England, China and many more.

Agroforestry has a long-established history in the UK spanning several centuries, representing a customary practice in rural landscapes where trees and shrubs were incorporated into agricultural systems to provide a diverse range of benefits. This includes traditional practices easily recognised in the English landscape, such as farm hedgerows and more contemporary and innovative systems such as silvoarable cropping. During medieval times, hedgerows with trees were utilised to demarcate field boundaries and provide windbreaks; however, the birth of modern agriculture and increasing emphasis on monoculture farming in the 20th century led to a decline in agroforestry practices, almost in concurrence with the rise of intensive agriculture.

Further reading: The History of Temperate Agroforestry

Declining agroforestry practices

Despite the manifold benefits associated with agroforestry, it has suffered diminished use and adoption, particularly in temperate ecosystems. This can perhaps be attributed to multiple factors detailed by Jo Smith, paraphrased here including:

The expansion of mechanisation resulted in the clearance of scattered trees to enable more efficient cultivation practices.

Post-World War II, there was an exponential increase in demand for agricultural productivity, ultimately leading to a preference for monoculture farming.

A decrease in agricultural workforces discouraged labour-intensive systems like full-stature fruit orchards.

The transition from small, fragmented land holdings to larger, consolidated farms led to greater field sizes, the removal of boundary trees and increasingly simplified landscapes.

Government policies favoured single-crop systems over diversified crop associations.

Historically, wooded areas were ineligible for subsidy payments, motivating the removal of trees to maximise subsidy income; trees and hedgerows were often considered financially inconsequential whilst livestock received substantially higher funding.

The implementation of stricter quality regulations for dessert fruit drove the intensification of orchard production, with improved fruit collection efficiency an additional factor; when one farm demonstrated profitability, others often followed suit to avoid financial hardship.

It was not until the late 20th and early 21st centuries that agroforestry experienced a resurgence in the UK driven by a growing awareness of its environmental and ecological advantages. Presently, agroforestry is increasingly acknowledged as a sustainable land management approach, promoting biodiversity, soil health and climate resilience while supporting agricultural productivity.

The potential for agroforestry (re)adoption

Agroforestry, (re)adoption is somewhat promising, albeit slow; according to Mukhlis et al, insufficient inclusion of agroforestry in public policy results in limited acknowledgement of its potential to address the climate crisis and enhance rural livelihoods. Moreover, a significant contributing factor to this could be rooted in the lack of availability of comprehensive evidence addressing the collective impacts of agroforestry on social, economic and environmental factors for communities. According to a study by Abdul-Salam et al, 2022, the barriers to greater agroforestry adoption are largely economic and include the following:

Monocultures in both agriculture and afforestation often generate higher returns than silvo-pastoralism, particularly when policy mechanisms do not incentivise carbon balancing through trees. Integrating these incentives could potentially change land use decisions.

The substantial upfront costs associated with land conversion can significantly affect farm finances.

The unpredictability of returns from forestry in comparison to agriculture.

The protracted production cycle of agroforestry and perception of land use decisions as irreversible.

The inherent loss of flexibility in land management.

In certain farming contexts, the potential impact on the food security of farm households.

The shortage of practical skills in establishing and maintaining trees.

Cultural resistance is rooted in the perception that farming and forestry compete rather than serve as complementary land uses.

Providing upfront financial incentives as support has been demonstrated to increase the probability of agroforestry adoption, concurrently resulting in the reduction of the rotation duration for forestry within these systems.

“Upfront support payments are shown to increase the likelihood of agroforestry adoption. They also have the effect of reducing the rotation length of forestry in such systems.” - Abdul-Salam et al, 2022.

Indeed, a regional study from August 2023 by Felton (et al) concluded that:

Around 60% of farmers in East and Southeast England would consider planting trees as part of agroforestry.

New planting would take up 5% of the current total farmed area, in relatively small areas (6 ha on average).

Farmers generally believed they would be capable of planting and managing new areas of agroforestry.

Farmers with low profit-maximising objectives were more positive towards agroforestry.

Further reading - Agroforestry guide for field practitioners

Overcoming challenges: A path forward for agroforestry

Notwithstanding the indisputable advantages of agroforestry, extensive adoption is inhibited by numerous challenges that necessitate resolution for it to increase:

A considerable knowledge gap exists among farmers and landowners unacquainted with agroforestry techniques and benefits; to remedy this, education and outreach programmes are critical to empower stakeholders to make informed decisions about the adoption of agroforestry practices.

A supportive policy framework is necessary to encourage the integration of agroecological frameworks and thus agroforestry into mainstream agriculture; governments can provide incentives such as grants, subsidies and tax breaks to render agroforestry financially viable. Clear regulations that address land tenure, tree planting and land-use planning are crucial.

Continued research is necessary to optimise agroforestry practices for the UK's unique climatic conditions and agricultural landscape - research can inform decisions about suitable tree-crop combinations, planting densities and maintenance practices. This is particularly relevant in the face of our ability to adapt to future climatic changes.

Effective agroforestry necessitates meticulous planning to determine the optimal arrangement of trees, crops and livestock; integrating agroforestry into land-use planning at regional and local levels can maximise its benefits and minimise potential stakeholder conflicts.

Initial establishment costs and lack of financial incentives can be a barrier for farmers and landowners interested in adopting agroforestry: developing funding mechanisms such as low-interest loans, grants or investment funds can alleviate financial constraints and promote wider adoption. Or you can come and ask 9Trees and our sponsors for help!

Further reading - FarmEd Challenges to UK Agroforestry

Conclusion

Agroforestry offers a promising solution to the agricultural and environmental challenges currently confronting the UK and could significantly contribute towards reaching net zero in the next decade. By embracing this comprehensive approach, the nation can cultivate resilient landscapes that integrate the often conflicting forces of nature and agriculture. Through initiatives such as education, policy reinforcement, research and community involvement, the country can fully unlock the potential of agroforestry, thereby promoting a more ecologically sound and sustainable future. The intermingling of tree crops epitomises the harmonious coexistence between humanity and the natural world, fostering landscapes that are highly adaptive, productive and resilient in the face of an unpredictable future; the relevance of agroforestry in a climate change policy context is rapidly emerging as an effective, adaptive nature-based solution for our uncertain times.

Further reading - 9Trees Special Planting

Agroforestry:

We will also be supporting biodiversity planting - Hedgerows and Uplands Projects and everything in between!

Biodiversity:

£25 Annually

Businesses can also get involved - Drop us an email about a BESPOKE approach!

#Agroforestry #SustainableLiving #Biodiversity

By Neil Insh - Researcher