Lifeblood: How healthy forests create healthy rivers and seas

‘ If you want to catch a fish, plant a tree’

– old Japanese proverb

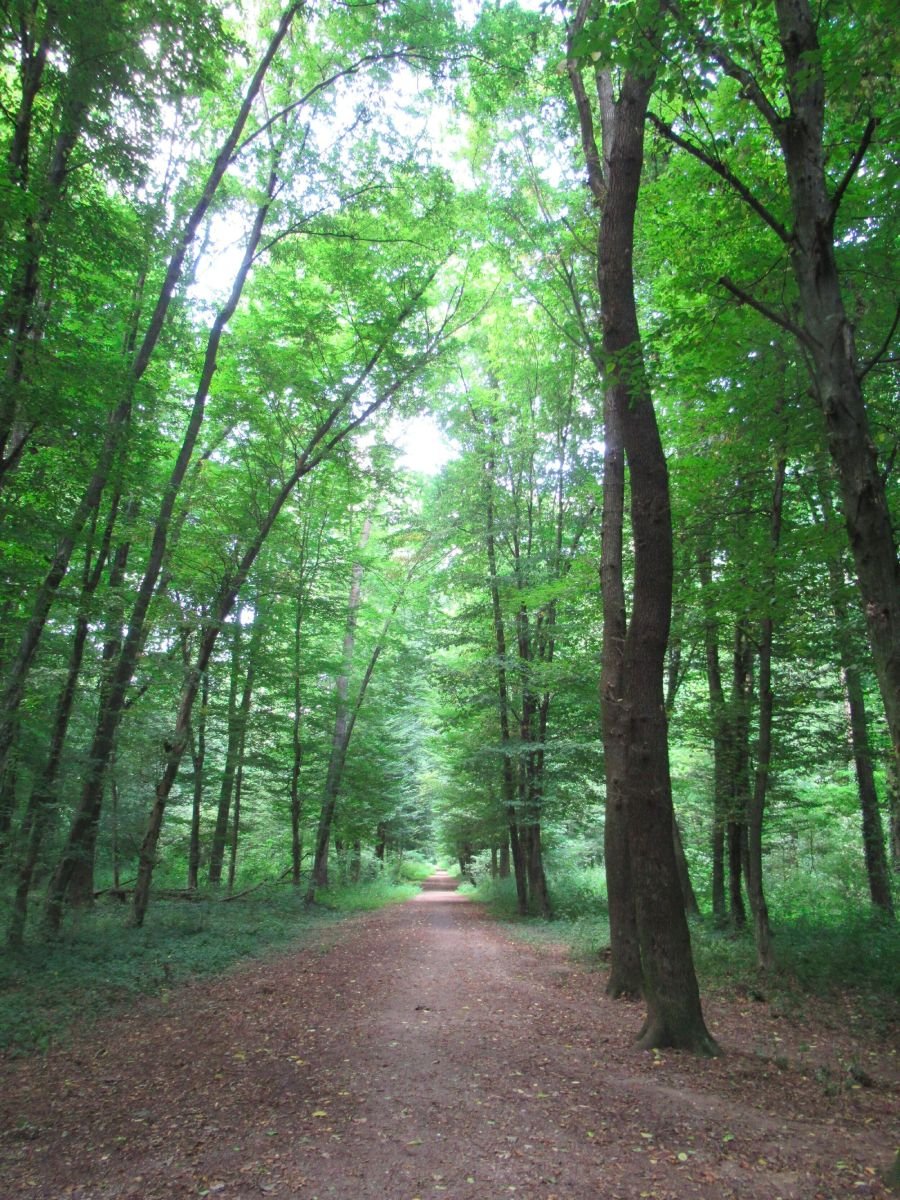

To walk around a woodland at this time of year is an exercise in the admiration of nature’s beauty. The trees, hawthorn, hazel, maybe elm, are beginning to bud, their fresh green tips foretell of the turning of the year.

Overhead the bird’s melodies announce the coming of the spring dance, the ancient ritual whereby all life surges forth to reawaken the land from its winter stupor. While there is still a fresh bite to the air, and the white blackthorn flowers put in mind the distant snows of months past, the sun gets warmer by the day, more golden in its reach. Maybe the smell of primrose or wild garlic hangs in the air, floating butterflies upon its perfume and drawing us out to greet the day, inviting us to walk once more amongst the wildest of corners of our landscape.

As you meander through these newly blossoming woods the chances are your mind will not be far beyond their bounds. They offer so much at this time of year and our focus can become dazzled by their beauty, however, the woodland is but a part of the wider landscape. An integral part whose presence is felt far from their alluring shade, in ways that we are only just beginning to comprehend. Water is one of the elements of the landscape that woodlands and forests influence in a positive way. Be it the slowing of water run-off from heavy rains, the filtering of water before it reaches the rivers or even the creation of rain thanks to the accumulated transpiration of trees and plants, the woods are a key part of the water cycle. Water and trees are intimately linked, albeit in a subtle, often overlooked way.

This relationship, like water that falls high in the mountains, travels an awful lot further than we may think. The old Japanese proverb above hints at how forests and trees are innately linked to the health of marine and freshwater fish stocks, and now scientific research has supported that claim.

Katsuhiko Matsunaga is a Japanese marine chemist, who has spent his life doing research that has shed light on the biogeochemical cycles of marine and freshwater environments. Some of this research has shed light on how forests are linked to the oceans in ways our ancestors had observed but we are only now beginning to understand.

In a 2002 article, Matsunaga helped demonstrate a correlation between bioavailable iron in the marine ecosystem, and multispecies phytoplankton growth. Phytoplankton are the basis of marine food webs. They are the primary producers, turning sunlight into energy, that provides zooplankton and fish with food and energy to be passed up the food chain.

This, at first glance, may seem irrelevant. However, previous research by Matsunaga suggests that the type of bioavailable iron that helps fuel this primary productivity is born from, and strongly correlated with, the forest soils found in the catchments of rivers. I don’t understand the chemistry, but in laymen’s terms the humic compounds and acids that form as leaf litter decays, bind with iron in the soil and are flushed into the river, then carried out into the ocean. This delivers the necessary bioavailable iron to the oceans, which are naturally low in iron, in a form that can be used by the phytoplankton.

They use it, they grow better and thus there’s a stronger foundation to the rest of the food web. This means a healthier ecosystem and more surplus fish to be caught. So, maybe there is some truth in the Japanese proverb. The below case study illustrates this connection.

Grandpa Oyster

Shigeatsu Hatakeyama is an oyster farmer from Japan who was familiar with Matsunaga’s earlier works and also the works of an American scholar John Martin. Back in the 80’s Hatakeyama came to understand how closely linked the forests and the oceans are thanks not only to his studies but also experiences gained when he was invited to the Loire estuary in France, a highly productive oyster growing area. He saw how the rivers leading to the estuary were covered in trees and realised how this was perhaps a key part of the Loire fisheries productivity. On his return to Japan, he instigated a campaign of tree planting in the river catchments that fed into his oyster beds. Productivity increased as phytoplankton reaped the rewards of the forests planted along the rivers, and the extra bioavailable iron they provided. Importantly, this increase in the fertility of his fishing grounds not only increased harvests but also built the resilience of his oyster farm and the wider estuarine ecosystem.

In 2011 there were earthquakes, and a tsunami, that hit his part of Japan. He lost everything but, thanks to his careful and coordinated scheme of reforestation to increase the health and fertility of his fishing grounds, he was soon up and running again, benefiting from the resiliance he had helped to create in the ecosystem. He now tours local schools trying to teach children the importance of the forests to the oceans, and hopes people will think more about this connection at all levels of decision making process.

Hatakeyama received the UN Forest hero award for his work.

There we have it, forests, trees, water and the oceans, are all more closely linked than we may realise when ambling around our favourite woodland. There are so many other ways in which forests and water are entwined in life and being. I hope to explore some of these in a later blog post.

Links:

Katsuhiko Matsunaga’s research

Grandpa Oyster - example of sustainable ocean business

Richard Nokes is a countryside professional specialising in habitat restoration and conservation through heritage skills such as drystone walling or hedgelaying. He believes in a countryside where people pursuing traditionally land management systems, repurposed and made relevant for the modern age, can be a key part of sustainable landscape conservation where the needs of both people and nature can be met on equal and synergistic terms. He is based in the Westcountry and often wears silly hats.